We’re proud to share that David has been honored to be the recipient of the North Carolina AIA 2025 Gail Lindsey Award.

This statewide award recognizes architects who embody a passion and lasting commitment to community impact and design excellence…

David recently won the DeWayne H. Anderson award for Housing from Preservation NC at their annual conference in Asheville. Awarded for his visionary leadership in promoting upper-level residential housing as a catalyst for downtown revitalization across North Carolina.

Last week our team attended the 2024 Preservation NC Conference held in Rocky Mount and Tarboro. Founded in 1939…

Crawford Brothers Steakhouse will be opening in Fenton later this year! The highly anticipated restaurant…

Exciting updates in Lincoln County! In 2022 the new Lincoln County Courthouse was opened…

Sneaky Penguin Brewing Company is quickly approaching its 2 year anniversary this October!

Monteith Construction’s new Raleigh office location is awesome!

While construction is ongoing at 122 Glenwood, the 3rd floor office space was completed earlier this year. Monteith relocated from their previous home on Morgan St to their newly renovated, historic Glenwood space.

Things are really heating up on Morgan Street since Wolfe & Porter opened earlier this year!

Some of you may remember 905 W. Morgan St as the dive bar Drink Drank Drunk and Atomic Salon; you also might recall the building was completely divided between the bar, the salon and the basement below.

In the fall of 2023 the owners of Heights House bestowed a unique honor upon the individuals and businesses who supported their vision and helped make Heights House the beauty it is today. They did so by crafting a menu that features 6 signature cocktails dedicated to and named after those who played an integral role in the design of Heights House. What’s more is they did it so thoughtfully; with each cocktail truly embracing the essence of its namesake.

If you’re in or visiting Wilmington, make sure and go to the corner of Castle & 3rd St. where you’ll find Olivero…Raleigh Chef Sunny Gerhart’s newest restaurant concept which couples spectacular Spanish-Italian-New Orleans themed fare and stunning design.

We are exceedingly grateful to be included in this Walter Magazine article!

This was such a fun project, and we were thrilled to partner with Janet to restore and repurpose this Historic Boylan Heights home. It’s always exciting when our team has the opportunity to work alongside someone who’s equally passionate about historical preservation.

Before the weekend hits, sharing a little preview of something big coming to Fenton in Cary!

As the Crawford Hospitality empire continues to expand, stay tuned for the much anticipated Crawford Brothers Steakhouse (projected to open later this year).

More to follow as the project progresses… but expect exquisite design, an epic lineup of dry-aged beef, and an extensive wine program!

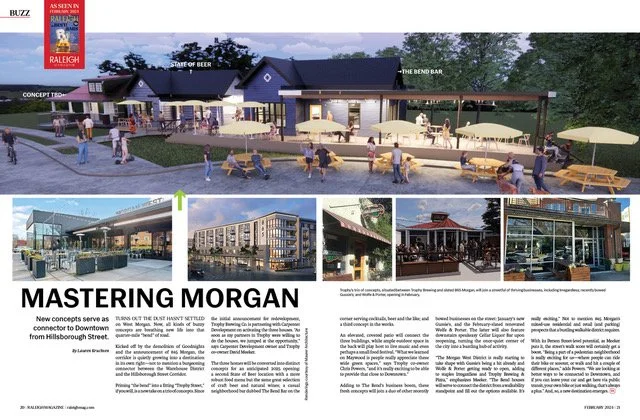

Between local favorites Trophy Brewing and Irregardless, sits a trio of houses located just as the road begins to bend towards Hillsborough St. In 2022 these buildings were purchased with a vision of bringing new life and purpose to the structures (which had fallen into a bit of disrepair), and a project aptly named “The Bend” was born.

On Monday in observance of MLK Day of Service we returned to Alliance Medical Ministry to volunteer in their garden. We were thrilled they were able to host us for the 2nd year in a row, and this year we even had some team member’s kiddos in tow to amplify our support!

Today David presented at the Historic Tax Credit Workshop in Albemarle, NC. This marked his 25th workshop presentation in towns across our state - sharing information and guidance on utilizing historic tax credits to encourage the rehabilitation of historic downtown buildings.

Figulina will soon be opening its doors and we hope you are as excited as we are!

Figulina Pasta & Provisions is bringing a fresh and exciting concept to the space previously home to Humble Pie (a beloved downtown staple for more than 30 years).

Construction is underway at 517 Pylon Drive! Soon to be Blue Co.’s 2nd location!

Swipe to see photos of the construction progress (and a few pre-construction pics). A previously blocked skylight was recently exposed and you know what that means…more natural light!

The Home of North State Consulting

Natural light, tin ceilings - Wilson has it all! This historic tax credit has space for a retail tenant on the first floor and will be the future home of North State Consulting. The original tin ceiling will be preserved as well as the historic skylight on the second floor.

Panther Branch Rosenwald School

The Panther Branch School closed its doors in 1956 and Juniper Level Missionary Baptist Church purchased the property in 1959, continuing to use the building as a meeting hall and social center until the 1980s. The school eventually fell into disrepair and a concerted effort to restore the historic building began in 2001 after the property was nominated to the National Register of Historic Places. A group of Panther Branch alumni came together and the JLBC Alliance was formed, incorporated in 2005 as a 501(c)(3) Non-Profit Organization. After many years of fundraising and events, the Alliance was able to begin initial planning on the phased project in 2009. Capital Area Preservation designated the building a Wake County Landmark in 2013 and Maurer Architecture became involved with planning the restoration of the building after the Alliance received a grant from the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Andrews Duncan Progress Update

Built in 1879, the Andrews Duncan House is a Raleigh Historic Landmark (1972), located in the North Blount St. Historic District and was individually listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1971. It has been unoccupied for many years after being used as offices for the State; the current Owners are restoring this gem into their own residence.

Heights House Looking Fresh!

Heights House recently got a fresh paint job. Unfortunately the owners were not able to go with their first choice of exposed brick due to some stubborn paint, but we think the darker pain looks pretty sharp.

Historic Lenoir, NC Building Brought Back to Life

This ca 1935 commercial building was on the brink of despair, with a collapsing roof and significant water damage, when David Maurer purchased it in early 2019. The first floor was originally an ice cream shop and then evolved into a restaurant and multiple later uses. The upper floor was originally the ice cream owner’s residence but later was transformed into three small apartments.

SALT Magazine – A spotlight on Wilmington development and several of our downtown historic projects!

Check out this awesome article in SALT Magazine – a great spotlight on Wilmington development and several of our downtown historic projects!